For a small side project I’m working on, I’m using a Sudoku puzzle solver and puzzle generator that I’ve written in Rust. The experience was fun, so I thought I’d write up a little bit about the algorithm I’ve used and some interesting stats about how it performs.

The Solver Algorithm

The first thing I built was an algorithm for solving Sudoku puzzles. After reading a bunch of Stack Overflow articles and a research paper or two, I came to the conclusion that the best way (and maybe only way) to write a solver is using a recursive solver that picks a value for a cell from the possible values left, and if it gets stuck it backtracks and starts over again with a different random value.

So in a bit more detail the algorithm is:

- Start at the first cell as the current cell

- Check to see if current cell is actually on the board (eventually, the current cell might be a cell that doesn’t exist). If it’s not on the board, return success, you’re done!

- Determine which values for the current cell are still possible by checking which numbers are not present in the cell’s row, column AND square.

- iterate through each of the possible values

- Set the value of the cell to the current possible value

- Recursively go back to step 2 with the next cell

- Check if the recursive call returned as success.

- If it did return success from the recursive call, else continuing iterating.

- If iterating completes without having returned success, return failure

Let’s write this as pseudo-code which might be easier to follow:

# assume we have a variable `board` which is our Sudoku board

# Function for recursively solving the board

# starting a index `cell_index`

def solve(cell_index)

# If we've made it to index 81, we've gone through all 81 cells.

# We're done!

if cell_index >= 81

return true

end

# The list of possible values: the intersection of values not

# already in the cell's row, column or square

possible_values = board.get_possible_values_at(cell_index)

# Keep track of the original value so we can set it back if all the

# possible values don't work

original_value = board.get_cell_at(cell_index)

# iterate through each value

possible_values.each do |new_value|

# Set the cell to the new value

board.set_value(cell_index, new_value)

# recursively call solve, if this call returns true than the puzzle

# is solved if it's not we need to try the next possible value

if solve(cell_index + 1)

return true

end

end

# If we reach here, we could never find a possible value that if set,

# leads to a solved puzzle. Set the value back to it's original value

board.set_value(cell_index, original_value)

# return false since we know that current board is not solveable.

false

end

if solve(0)

puts "Board is solved!"

else

puts "No possible solution :-("

end

This should solve any puzzle that is solveable. Of course, there might be multiple ways to solve a given puzzle and this solver will only find one of them. Because it is deterministic (i.e., there is not randomness in how it solves), this solver will always return the same solution for a given puzzle.

Now that we have a solver, making a puzzle generator is easy.

Generator

In general our algorithm for generating puzzles that only have one solution is as follows:

- Start with a completely empty board

- Run the solver (ensuring that the iteration of possible values is random)

- Randomly remove a cell

- Run the solver again this time forbidding it from using the original number in that slot

- If the solver returns true there is more than one solution when that square is empty. Refill the square with original value

- If the solver returns false there is only the one solution. Leave the cell empty

- If you want to remove more cells, return to step 3. Otherwise you’re done.

There are two capabilities that our solver needs to gain in order for this to work:

- The ability to choose randomly from a given cell’s possible values. Without this capability solving an empty board would always result in the same board. In other words, our solver until this point has been deterministic and we need it to not be.

- The ability to solve with constraints. In order to ensure unique solutions, we need to try to solve the puzzle without using the removed value.

Once we have these things our code can look something like this:

def solve(index, forbidden_index, forbidden_value)

# same implementation above except possible values

# are tried at random and we cannot fill the cell at

# forbidden_index with the forbidden_value

end

# Create an empty board

board = Board.empty()

# Solve the board

solve(0)

# Loop `number_of_cells_to_remove` times

number_of_cells_to_remove.times do

# Removing a cell might not work so we loop

# We'll `break` when we've successfully looped

loop do

index = random_cell_index

original_value = board.remove_cell_at(index)

if !solve(0, index, original_value)

# We couldn't solve the board without using the original value,

# The solution we had before was unique, we can leave it empty

break

end

# There was another solution meaning removing this cell

# doesn't leave a board with a unique solution, put the value

# back and loop again

board.set_value(index, original_value)

end

end

We now have a way to solve sudoku boards, and a way to generate them!

Some Interesting Benchmarks

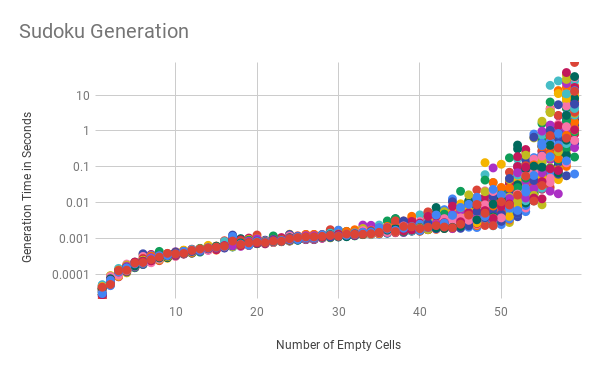

I was curious to see how fast the solver was at generating boards with ever increasing number of blank squares. The following is a chart of how this algorithm performs with the y-axis (the time of generation) plotted on a logarithmic scale:

Clearly things are pretty quick for generating puzzles with anywhere between 1 and around 40 blank cells.

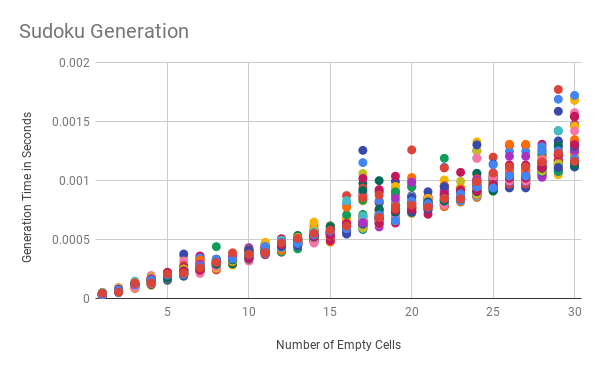

Here’s a zoomed in picture of the generations with 1-30 blank cells with the time scale no longer logarithmic:

From 1-30 things grow relatively linearly. Increasing the number of blank cells by one generally leads to the same overall decrease in performance.

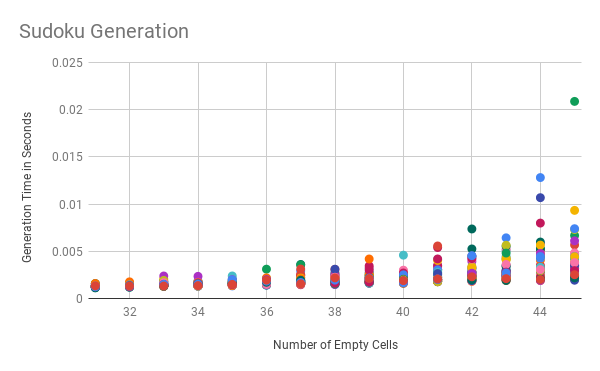

Now let’s take a look at 31-45 where performance starts getting shacky:

The variance between different runs is starting to grow. Interestingly the lower bound of runs continues to grow linearly.

After 45 the variance continues to grow and grow.

Once we reach 55 and above then the performance is completely unpredicatable, sometimes taking upwards of 10s of seconds (and even one run of over a minute) to complete while others still complete in well under a second.

If you want to take a look at the data yourself, you can find it here. What do you find interesting about it? Let me know on Twitter!